"Let there be light" is a good title for this heap of Pola-geekery blog fodder, and we're gonna get down and dirty on this one with lots of cross-eyed tech talk, and a smattering of pre-school physics. If that wasn't enough, there's a bunch of obscure pics that will both confuse and astound you. It's the only way I know how to explain it.

___________________________________

Just about every Model 1 SX70 I get in the shop to fix up has some sort of overexposure problem. Images are faded, overexposed, highlights are heavily washed out, there's zero contrast, and some objects are barely visible in bright scenes. Some shots even have a slight blur to them. There's many variables that can affect exposure metering on the SX70 (sticky shutter blades, sluggish S1 solenoid, incorrect faceplate ND filter, LTO - long time out), but the most common is a crunchy-crusty photodiode filter.

Overexposed indoor/outdoor shots caused by a heavily blocked photodiode filter.

The SX-70 was designed to "see" ambient light by means of a photodiode that is built into the shutter's circuit board (ECM - electronic control module) which is mounted right behind the shutter frame. What exactly is this "the photodiode"? Well... simply put, a photodiode is simply an electronic component that takes light and converts it into electricity.

Symbol for photodiode. Ever see Stargate? Well... those symbols were constellations but this looks like one of em... whatever. Read on.

When the shutter button is pressed and the internal mirror flips up, the exposure sequence begins. The shutter blades open to reveal light to the photodiode through secondary aperture holes located right behind the faceplate's "electric eye" (which is nothing more than an ND filter held into place by a pretty chrome ring bezel). Light is converted into electricity that runs into a capacitor on the ECM. When that capacitor is full, it pukes out it's charge in one huge burst which is read by the shutter's IC "brain" and tells the shutter blades that it's time to close the doors, ending the exposure part of the cycle. The remainder of the cycle then mechanically spits out the exposed print.

Shutter assembly cutaway showing the shutter blades. Secondary aperture holes are shown to the right of the blades. Located behind these openings is the photodiode.

A good way to understand how the automatic light metering system of the SX70 works is this:

- The less light that hits the photodiode, the longer for the capacitor to charge and the shutter blades remain open for a longer amount of time.

- The more light that hits the photodiode, the faster for the capacitor to charge and the shutter blades remain open for a shorter amount of time.

Keeping the above comparison in mind, because of low levels of ambient light, a lot of indoor shots without a flash or tripod are blurry. The shutter blades remain wide open for a few seconds and any camera movement results in blur. I'm gonna pat myself on the back for that explanation... ready for that second cup of coffee and a valium?

So back to the crusty photodiode filter. The photodiode itself is protected by an opaque housing and only light can get in through a little glass window. This window, filtering out any type of unwanted and interfering light that may cause inaccurate readings, is a tiny green glass gel filter. Without this filter in place, the photodiode lets in tons of nasty light that can't even be seen, throws off the reading, and results in way too fast of a shutter speed. Shots then emerge very underexposed and dark.

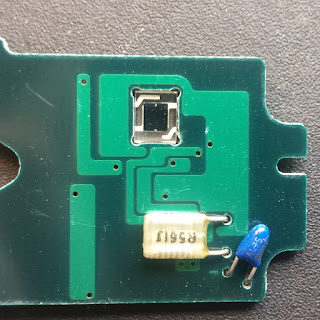

A very clean photodiode filter on an SLR680 (note the conformal coating only surrounds the housing and traces leading to the capacitor).

The SLR690 also has a similar photodiode but the filter is built directly into the shutter frame.

As far as what the residue is that grows/leeches out of/accumulates on the filter... I haven't identified that yet. Anyone that has studied optics, chemistry, or even internal medicine, please feel free to jump in on this one. I'm thinking of sending a sample to a lab (a sweet cop-show crime lab) to see what it actually is, but it's most prominent on Model 1s that seem to have been stored in wet conditions. The moldier the camera, the crustier the filter. One of my theories is that it's a reaction between the adhesive used to bond the filter into the photodiode housing and moisture, much like the corrosion on a car battery. Or it could be a reaction to moisture and the glass itself? This corrosion is white, very opaque, and can drastically reduce the amount of light that reaches the photodiode. Remember what I wrote above about the less light that hits the photodiode? Yep... shutter stays open longer. Overexposure.

Crusty crunchy corrosion on a car battery... yuk.

Crusty crunchy corrosion on an Alpha 1 ECM photodiode filter which will cause overexposure... More yuk. You can tell it's unfavorable since the word "crap" is written by the area circled.

Wonderful! So what now? Easy!... remove the corrosion. Often times the corrosion is found on the outside of the filter and it's as simple as using a blade and then some al-kee-hol to remove the gunk. Later model ECMs with an epoxy conformal coating (Texas Instruments would dip the edges of their circuit boards in to a black epoxy) are usually easiest to clean possibly because the coating gave better protection from moisture. Except for extremely moldy cameras, most corrosion found on these models is only limited to the outside of the filter. Alpha 1s, Sonars, 680s, and some late model Model 1 circuit boards have this black epoxy coating. But Model 1s from 73-75 had a different urethane/lacquer type coating that didn't offer as much protection and often times the corrosion would occur on the inside of the filter as well. Early 72-73 Fairchild ECMs didn't have any coating at all.

White crusty deposits on the inside of the filter adds a whole additional level of "meter cleaning" and the photodiode housing needs to be rebuilt. Essentially the filter needs to be cut out, the gunk removed, the filter bonded back into place, and the housing resealed. It would be easy if the filter was nice and flexy but it's a fraction of a mm, thin, tiny piece of glass that if not removed properly, can crumble. Ask me how I know this... that little sucker is like an eggshell.

Nice and clean photodiode filters. The one on the right chipped during removal. Oops.

1. A blocked/corroded photodiode filter on a standard Model 1.

2. Simply cleaning the front of the filter reveals there is still blockage on the reverse side.

3. The filter is carefully cut out and fully cleaned.

4. The filter is bonded back into position and the housing edge is resealed.

Cleaning or rebuilding the photodiode filter allows for proper light readings and accurately exposed prints. There's ways to "kinda" fix it, like cranking the LD trim wheel all the way to dark or even removing the faceplate ND filter (which by the way was used to fine tune final exposure and varies from camera to camera) but these are simply band-aid methods that don't allow the camera to operate properly like it was designed and may work in one type of lighting but not in others. There are many additional variables like film chemistry that can affect results as well. One company has gone as far as designing and manufacturing their own ECMs to avoid restoring old technology. I'm straight up green with envy on that one but I don't even have a slight fraction of the capital they do to put toward R&D and manufacturing for an SX70 circuit board so I had to learn how to restore the old stuff... which I find more fun anyway.

Accurate light metering = proper exposure. These were taken with a '73 Model 1 with a rebuilt photodiode housing.

So there you have it regarding the SX70 photodiode/filter, but I have to end this screed with a little 2nd Shot plug - A primary part of my repair process involves checking/cleaning/rebuilding this filter on every model camera that comes into the shop. This falls within my mission statement that if the camera "kinda" works, it's not working properly. This camera relies on all sequences working 100% for optimal results. I like optimal results.

-queue music "Live to Win"-

-strong upward fist pump-

-fade out-

-end scene-